Today I presented at Scala By The Bay about my project to build a search engine for data structures. I’ve deployed the project at ds.shlegeris.com; you can play with it there. (EDIT November 2017: I took this down.) You can also read the source code on Github.

This blog post is a more detailed version of the talk I gave today.

You can also watch the talk:

A search engine for data structures

A data structure is a way of organizing data to efficiently support a particular API. So a data structure search engine is a program which takes an API and returns an efficient implementation.

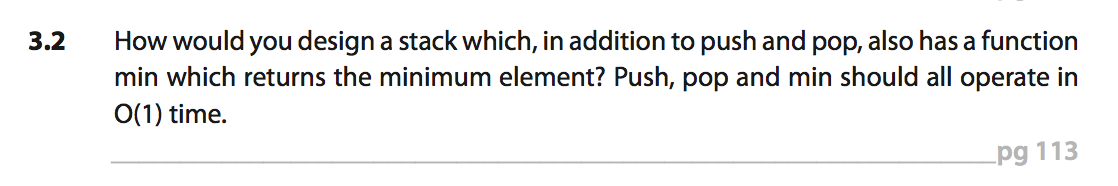

Let’s look at some examples of queries that the search engine is able to support. Here’s one from Cracking the Coding Interview:

You can see the answer my software finds here.

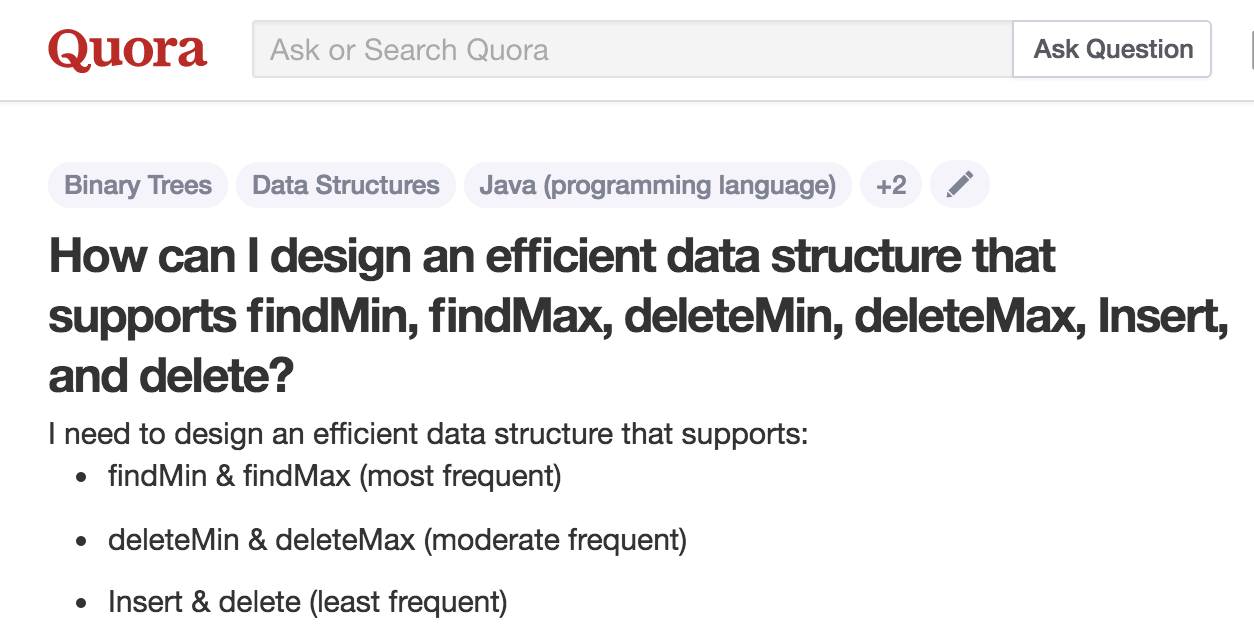

Here’s one from Quora:

And here’s my answer.

Here’s a third Quora question:

The pattern here is that we are being asked to choose a fast data structure to support a given set of methods. I’m going to call that set of methods an abstract data type, or ADT for short.

Implementation

The whole project is built around a bank of knowledge about data structures and the relationships between different methods.

The core algorithm is something like the following pseudocode:

def chooseFastDataStructuresForAdt(adt: AbstractDataType): Set[DataStructureChoice] = {

val options: Set[DataStructureChoice] =

allDataStructures.subsets

.map((subset) => findAllTimes(subset, adt))

adt.pickBestCompositeDataStructures(options)

}

So we compute the times taken for all the methods by each possible composite data structure. Then we choose the best data structures for our use case.

Inference on method implementations

To do this kind of inference, we need to be able to evaluate the runtimes of all methods of a particular composite data structure. Let’s look at how that works.

Throughout this whole thing I’m going to assume we’re talking about methods on an ordered list.

We need to talk about lots of different methods, like getFirst, getNext, getByIndex. These are redundant on purpose. In an array, it’s natural to define getByIndex and derive getFirst and getNext from that. In a linked list, the other way round is nicer.

We will describe the read methods of an ArrayList like this:

ds ArrayList {

getByIndex <- 1

}

And a linked list will look like this:

ds LinkedList {

getNext <- 1

getFirst <- 1

}

The central relationship that we care about is how implementations can be used to implement other things. Let’s make some rules like that:

getByIndex <- getFirst + n * getNext

getFirst <- getByIndex

getNext <- getByIndex

So you can implement getByIndex with O(1) calls to getFirst and O(n) calls to getNext. You can also implement getFirst or getNext with O(1) calls to getByIndex.

Facts of this type are called ‘implementations’ in my system; they have the class Impl. Implementations can either belong to data structures, like getByIndex <- 1 above, or they can be universally true, like getByIndex <- getFirst + n * getNext.

There’s a useful distinction between implementations with free variables (like f <- g) and those without (f <- 1). I call the former type free and the latter type bound. Bound implementations are a subset of free implementations. I represent these with the classes FreeImpl and BoundImpl. (These names aren’t great, I’d be happy to hear suggestions for better ones. In lambda calculus a term with no free variables is called a combinator, but almost no-one would actually think that’s an intuitive term for what I’m talking about here.)

Parameterization

Additional complexity comes from the fact that implementations can be parameterized, and can have conditions attached to their parameters. For example, the method reduce[f] is parameterized by the function it’s reducing. The difference between a method being parameterized and it taking an argument is that the parameter must be known at the time of data structure initialization.

For example, if I want to have a list which maintains its sum, I can just store the sum as an Int somewhere, and add new values to my sum as they’re inserted and subtract them as they’re removed. This is possible because + is invertible. So I want to be able to write down a data structure for maintaining this kind of reduction. (simplified from here)

ds InvertibleReductionMemoizer[f] if f.invertible {

reduce[f] <- 1

insertLast! <- 1

deleteLast! <- 1

// you can do this anywhere if f is commutative

insertAtIndex! if f.commutative <- 1

updateNode! if f.commutative <- 1

deleteNode! if f.commutative <- 1

}

This data structure lets you push and pop values and maintains the reduction for any invertible function f. In addition, if f is commutative, you’re allowed to do random modifications to the list.

These constraints need to be propogated through the code. For example, my code contains these implementations:

getMinimum <- getFirstBy[valueOrdering]

getFirstBy[f] <- reduce[_{commutative, idempotent} <- f]

The getFirstBy implementation means that you can implement getFirstBy[f] by using reduce with a parameter which is commutative and idempotent, and which requires calling f every time it is called.

We still have the distinction between free and bound implementations: f[x] <- x is bound and f[y] <- z is free.

Searching through implementations

To search for method times for a given data structure, we start out by taking the union of all the implementations for a data structure and all the universal implementations, so in the case of the LinkedList above we have

getNext <- 1

getFirst <- 1

getByIndex <- getFirst + n * getNext

getFirst <- getByIndex

getNext <- getByIndex

reduce[f] <- getFirst + n * getNext + n * f

We want to end up with a map from methods to their final cost. To do this, we will basically graph search over our Set[Impl]. The code for that search looks something like this (real version here):

def getAllTimes(implementations: Set[Impl]): MethodTimes = {

val result = new MethodTimes()

val queue = mutable.PriorityQueue[BoundImpl](implementations.filter(_.hasNoFreeVariables))

while (queue.nonEmpty) {

val impl = queue.pop()

// add impl to the result if it isn't already in there

if (result.implIsUseful(impl)) {

result.addImpl(impl)

implementations.foreach((neighbor: Impl) => {

if (neighbor.uses(impl.methodProvided)) {

// Take the neighbor, like `getByIndex <- getFirst + n * getNext`

// and see if it can be used -- in this case, seeing whether you have

// a time for both getFirst and getNext. If so, push it to the queue.

// this can return multiple things in the case of

// parameterized implementations

neighbor.bind(result).map((boundNeighbor: BoundImpl) => {

if (result.implIsUseful(boundNeighbor)) {

queue.push(boundNeighbor)

}

})

}

})

}

}

result

}

The bind method of Impl only returns a non-empty set if it can substitute out all the free variables in the right hand side of the Impl. For example, bind will return getByIndex <- n when called on getByIndex <- getFirst + n * getNext with a result set containing getFirst <- 1 and getNext <- 1. But it will never return something like getByIndex <- getFirst + n.

For non-parameterized implementations, there is always a fastest way of doing them. This isn’t true for parameterized implementations, because different implementations might have different conditions and costs which don’t strictly dominate each other. For example, the implementations

foo[f] if f.bar <- 1

foo[f] if f.baz <- 1

foo[f] <- n

foo[f] <- f

are all useful in different situations, so we want to return all of them.

(In practice, I haven’t needed to use this expressiveness very often, and it does make my code much more complicated. So I think I might regret adding it. I’m not sure yet. Certainly it’s useful to be able to pass conditions around, I’m not so sure it’s important to be able to refer to bound variables in the RHS of your Impl.)

Composing data structures

When you have a composite data structure, you only have to run your read methods on one of the data structures, but you have to run your write methods on all of them.

However, the write methods of one data structure can rely on read methods of another. Consider again the single Int which we can use to maintain the sum of a list. On its own, it doesn’t support deletion methods like deleteLast. But if it is paired with an ArrayList, it can use the getLast method of the ArrayList to find out what it needs to subtract.

So we end up with code approxiately like this (real version here):

def getAllTimesForDataStructures(dataStructures: Set[DataStructure]): MethodTimes = {

// for the read methods, union everything provided by the data structures

// with the defaultReadImpls, then search for times with it

val allReadTimes = getAllTimes(dataStructures.flatMap(_.readImpls) ++ defaultReadImpls)

// calculate all write times separately

val writeTimesForDataStructures = dataStructures.flatMap((ds) => {

getAllTimes(ds.writeImpls ++ allReadTimes)

})

// add them to each other

val overallWriteTimes = writeTimesForDataStructures.values.reduce(_ leastUpperBound _)

allReadTimes ++ overallWriteTimes

}

And now we can find optimally fast composite data structures!

Parameterizated data structures work very nicely with this, albeit in a slightly counterintuitive way. Basically, during the search we ignore the fact that an InvertibleReductionMemoizer[f] has to actually choose a single value of f; we let everyone use the reduce[f] Impl without reservation. At the end of the search, we can figure out how many different instances of InvertibleReductionMemoizer we actually need: perhaps we need one for getSum and one for getXor or whatever other implementation we wanted to memoize. The number of instances of a data structure that we require only affects our write times by a constant multiple, so it’s irrelevant for the search we’re doing here.

The main other complexity is that the search needs to maintain its paths: we want to be able to know which data structures were used for which methods. This is maintained by storing this source information and passing it around with the implementations throughout.

Optimizations

One obvious problem with this is that there are exponentially many potential composite data structures to look at. So I use some simple heuristics to cut down the number of composite data structures that I actually consider.

Firstly, data structures are only considered if they have a read method which could plausibly help with the implementation of one of the read methods in the ADT. “Could plausibly help” is determined by considering the directed graph formed by turning an Impl like f <- g + h into the edges g -> f and h -> f–if there’s a path in that graph from x to y, a data structure providing x could plausibly help with an ADT requiring y. This usually cuts off half of the 15-or-so data structures I have, which makes things like 50 times faster. This logic lives here.

Secondly, when searching through subsets, if I figure out method times for the set of data structures \(\{A, B, C\}\) and I’m considering looking at the set \(\{A, B, C, D\}\), I look at whether any of the implementations provided by \(D\) are useful given the result of \(\{A, B, C\}\). If not I don’t explore any subsets including all of \(\{A, B, C, D\}\). Here’s the source. This makes things a few times faster.

I also cache results of calls to getAllTimes. If I’ve established that the read method foo takes \(\log(n)\) time for the set \(\{A, B, C\}\), then I can immediately put the Impl foo <- log(n) into the queue when running the search on \(\{A, B, C, D\}\). I am not sure if this improves efficiency.

Deployment

The code is deployed as a Finagle server with a React app in front. The React app can display useful information about the internals of composite data structures.

I tried compiling my search code to ScalaJS, but it was too slow to be a pleasant experience. If my code was like 10x faster it would be alright.

Further work

Here are things I want to do:

- Generate real code. The result already has all the information we need to generate code, I just haven’t put in the effort to make it work yet.

- Acquire users. I plan to use this to answer lots of questions on Quora etc, to get people to look at it, and hopefully people will start using it more regularly.

- Consider other optimizations. I added in a bunch of cruft in the final push before the conference presentation, and it’s possible that some refactoring might speed things up.

- Distinguish between different concepts like average case time, worst case time, and amortized time.

- Instead of minimizing asymptotic time, I could instead get an empirical measure of the speed of different methods in different data structures, and choose the fastest data structures for a given expected data set size using those measurements. This works best with the approach where we are generating real code with real data structure implementations.

- Extend to talk about other types of queries. In particular, I could try to support more SQL-style queries on multi-column data.

Conclusion

How useful could a tool like this be? I don’t know. A lot of data structure research can’t yet be fit nicely into the framework of things I can describe with this system.

I also find that writing data structures down for this project forced me to think about them and write down facts about them that aren’t usually said. For example, the sparse table data structure for range minimum query is usually not described as letting you push things on the end in amortized \(O(\log(n))\), even though you can obviously do that by resizing exponentially. This forced clarity is really useful.

Overall the practical usefulness of this project remains to be seen. It was a lot of fun to build though.

Thanks heaps to everyone who helped me out as I was writing this.

Appendix: how long did I spend on this?

According to RescueTime, I’ve spend 94 hours in IntelliJ this year. Almost all of that time was spent working on this project. A lot of the time I spent working on this project is not included in that number: the frontend was written using Sublime Text, and I had to spend a lot of time thinking in front of a whiteboard, and I spent the usual amount of time on StackOverflow or in a terminal.

My subjective experience is that I spent a bunch of time on this on most of my weekends and many of my evenings for the past two months. If I did on average four hours of work on each weekend day and ten hours of work over the week, that’s 14 hours a week times 8 weeks = 112 hours. I also took off two days from work to work entirely on this, and got about 8 hours done on each of those days.

When I feel like I am working on my software, I also often end up reading Facebook or whatever for 25% of the time. So the 94 hours I spent in IJ probably also involved spending an extra 30 on the internet.

My overall guess is that I spent between 150 and 200 hours on this project.

Appendix 2: Scala libraries used

- FastParse is a parser combinator library. It’s amazing–it’s by far the best experience I’ve ever had writing a parser. The docs are reasonably good. Li Haoyi, the author, is super responsive on Gitter to answer questions, and he even helped me in person when I was stuck on something while making some last minute changes at Scala By The Bay :smile:.

- ScalaTest is a fine testing library; no complaints, but it’s not particularly inspiring.

- QuickLens is amazing! It’s a super simple and easy-to-use lens library. Lenses are a tool for solving the problem of nested updates in immutable data–if I want to get a copy of my nested list, but with the first element having an incremented

fooattribute, it lets me write something likenestedList.modify(_.head.foo).using(_ + 1). Strongly recommend! - Scalactic gives you a

===operator, which checks equality and throws a compile error if you’re doing a futile equality check. Strongly recommend!